Archive

Art, Politics, Paradox

Yesterday I saw John Pilger speak at the London Anarchist Bookfair. It was heartening to see that he continues to see value in speaking truth to power, and challenging it’s various forms. He admirably challenges the corrupt behaviour of those in power around the world. I have a lot of respect for someone who can maintain their integrity over as many years as he has, and still manage to deliver some quality investigative journalism.

However, a throwaway comment that he made got me thinking. In fact, I found what he said illuminating and rather disappointing. Pilger was asked why it is hard to get people, especially young people, engaged in political activism, in criticising the system in a thoughtful and productive way, and then acting on their thoughts in a collective way. One of the things he said in response to this question was that (he said this with a bit of a sneer on his face) young people ‘have postmodernism nowadays’ (?!) to ‘keep them distracted’. I am not really sure what he meant by this, but what I think he meant (given the context he said it in) is that there is too much moral ambivalence, there is no ‘Truth’, everything is relative and today’s culture seduces and distracts us from the ‘truth’. This comment got me thinking about why some of the major critics of power can see things in such a simplistic way. I remembered how similar Pilger sounded yesterday to the late playwright Harold Pinter in his 2005 Nobel lecture, which was pre-recorded as he was too ill to travel to Stockholm to receive his award. And then I remembered a paper I gave a while ago at a number of conferences, which addresses this question, and looks at how a philosopher, TW Adorno, can help us to understand this simplistic and rather unhelpful approach. I called it ‘Art, Politics, Paradox’. It’s quite long, but I have posted it here. I have posted the abstract first so that you can see if you would like to read the paper once you know what it’s about. As usual, all comments are very welcome.

The Abstract:

It might seem that Harold Pinter and Theodor W. Adorno have little in common. The former, a dramatist and poet who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2005, is also an outspoken political activist. The latter, a philosopher, musicologist and critic of the ‘culture industry’ is not usually associated with Pinter’s kind of public dialogue, indeed, he has often been mistakenly caricatured as an “aloof mandarin”. However, in the light of British academia’s renewed interest in Adorno, the question of the continuing relevance of his work needs to be addressed. In this paper, I argue that Adorno’s relevance can be gauged through the exploration of some of the contradictions and tensions in his writings on art. Essentially, it is in these contradictions and tensions that we find Adorno ruthlessly questioning notions of truth, experience, the political, and the limits of philosophy itself. In order to illustrate this argument, I explore a rather illuminating dialogue between Pinter and Adorno, focusing on how each thinker conceives of aesthetic truth. In his Nobel acceptance speech, Pinter argues for two kinds of truth, aesthetic truth (which is open, ambiguous and flexible) and political truth (which is, he says, ‘accurate’, and ‘real’). Adorno, on the other hand, argues for two kinds of aesthetic truth, although they are also polarised; one account of truth is anti-essentialist and the other is absolutist. I explore these various accounts of truth, arguing that the similarity between Pinter and Adorno lies in each thinker’s paradoxical construction of truth. I argue that what is interesting is how each thinker confronts the paradox that he constructs.

I go on to claim that Pinter presents us with an interesting problem: unlike Adorno, he resolves his paradox. For political reasons, Pinter sacrifices aesthetic truth for political truth. He argues that we must reject the ambiguity and elusiveness of dramatic truth and assert political truth in order to expose the lies of the powerful. Thus Pinter privileges absolutism over anti-essentialism and absolutism wins the day, which in effect leads to the scepticism he is trying to avoid, and contradicts his political commitment to democracy. What I take issue with here is the idea that there has to be resolution; Pinter refuses to concede to paradox or even ambiguity in his work. However, Pinter is not necessarily right about this; one can live with contradiction, indeed, I would add that one should. This is where Adorno is more successful: Although his account of truth is also paradoxical, the dialectical negativity that Adorno maintains through contradiction and tension requires that his paradox is sustained rather than resolved. Thus Adorno strives to avoid absolutism, although this attempt often, and inevitably, fails. But failure is insignificant. For it is in this attempt to negate absolutes, in the non-identical, that we find the space for reflection, speculation, interpretation and, thus, perhaps freedom and the good. It is here that we find the considerable ‘ethical and political force’ in Adorno’s work. I conclude by arguing that Adorno shows us philosophy’s continuing significance for orienting ourselves in today’s complex world lies in asking pertinent questions, rather than searching for answers.

Pinter’s Nobel Lecture is recorded here:

http://nobelprize.org/mediaplayer/index.php?id=620

The paper:

It might seem that Harold Pinter and Theodor W. Adorno have little in common. The former, a dramatist and poet who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2005, is also an outspoken political activist. The latter, a philosopher, musicologist and critic of the ‘culture industry’ is not usually associated with Pinter’s kind of public dialogue, indeed, he has often been mistakenly caricatured as an “aloof mandarin”. However, in the light of British academia’s renewed interest in Adorno, the question of the continuing relevance of his work needs to be addressed. One way in which we might address this issue is by loosely comparing how Pinter and Adorno conceive of truth in art and in the political.

In his Nobel acceptance speech, Pinter develops an interesting distinction between aesthetic and political truth. He argues that the language of contemporary politics has thrown his life as an artist and his life as a citizen into an unfortunate state of contradiction. Pinter conceives of this contradiction in terms of the different ways in which art and politics view ‘what is real and what is unreal…what is true and what is false’ (Pinter 2005. p. 9). For Pinter the artist, the ‘exploration of reality through art’ (ibid. p.9) reveals that language is full of ambiguity. Dramatic art presents us with many truths. He writes, ‘[t]hese truths challenge each other, recoil from each other, reflect each other, ignore each other, tease each other’ (ibid.).

What art shows us, Pinter claims, is that ‘a thing is not necessarily either true or false; it can be both true and false’ (ibid. p.9). Conversely, for Pinter, his life as a citizen demands that he reject the ambiguity and elusiveness of dramatic truth. This is primarily because, for him, mainstream politics is concerned with the exercise of power at the expense of truth. Pinter argues that ‘politicians…are interested not in truth, but in power and in the maintenance of that power. To maintain that power it is essential that people remain in ignorance of the truth, even the truth of their own lives’ (ibid. p. 10).  The United States, the most powerful country in the world, has a monopoly on language: in US politics, ‘language is actually employed to keep thought at bay’ and citizens are led to believe that what is false is actually true. This denigration of the truth, Pinter argues, is an affront to ‘our moral sensibility’ (ibid. p.12). In the present political climate, we should, more than ever, engage in the struggle to restore ‘what is nearly lost to us – the dignity of man’ (ibid. p. 13). Citizens are morally obliged to take a stand against this degradation of humanity by ‘defining the real truth of our lives and our societies’ (ibid. p.13). In his concluding statement, Pinter asserts that if we look for it, this ‘real’ truth will eventually manifest itself to us:

The United States, the most powerful country in the world, has a monopoly on language: in US politics, ‘language is actually employed to keep thought at bay’ and citizens are led to believe that what is false is actually true. This denigration of the truth, Pinter argues, is an affront to ‘our moral sensibility’ (ibid. p.12). In the present political climate, we should, more than ever, engage in the struggle to restore ‘what is nearly lost to us – the dignity of man’ (ibid. p. 13). Citizens are morally obliged to take a stand against this degradation of humanity by ‘defining the real truth of our lives and our societies’ (ibid. p.13). In his concluding statement, Pinter asserts that if we look for it, this ‘real’ truth will eventually manifest itself to us:

When we look into a mirror, we think that the image that confronts us is accurate. But move a millimetre and the image changes. We are actually looking at a never ending range of reflections. But sometimes a writer has to smash the mirror – for it is on the other side of that mirror that the truth stares at us (ibid.).

Pinter claims that that we have to recover our lost dignity as human beings by being determined in our assertion of the ‘real’ truth when we come across lies. If we smash the mirror, we find ‘real’ truth, the binding element that the community needs in order to claim back its dignity.

Here, we see that for the sake of the urgency of the task at hand, Pinter’s political self overrides his artistic self and thus the unequivocal wins the day. The ambiguity and uncertainty of creative thought is replaced by Pinter’s assumption that there is such a thing as ‘the real truth’ (ibid.) – we might think of this as absolute objective certainty – which can be found behind the mirror. Although it is impossible to disagree with Pinter’s demand that we stand up to the lies which politicians often claim to be true, it is also clear that if we follow this demand in the way that he conceives of it, something important is sacrificed. In effect, Pinter the artist, who maintains an interesting anti-essentialism, steps aside for the sake of Pinter the citizen’s political imperative. Thus, Pinter suggests that we privilege absolutism over anti-essentialism.

Pinter implies in his acceptance speech that there has to be resolution; it is impossible for him to concede to ambiguity or contradiction. However, Pinter is not necessarily right about this; one can live with contradiction, indeed, I would add that one should. Pinter’s ruminations on art, politics and truth have an interesting affinity with Adorno’s notion of aesthetic truth in his posthumously published Aesthetic Theory.  The affinity lies in the fact that, like Pinter, Adorno conceives of truth in two, apparently paradoxical ways. Unlike Pinter, however, Adorno both tries to resolve contradiction and attempts to turn living with contradiction into an ethical imperative. In fact, Adorno’s success lies in how he constructs multiple, dialectical arguments. He discusses aesthetic truth in ways which overlap, contradict and interplay, so that contradiction isn’t a problem and becomes a resource, which potentially informs our ethical and our political considerations. This claim clearly requires some elaboration.

The affinity lies in the fact that, like Pinter, Adorno conceives of truth in two, apparently paradoxical ways. Unlike Pinter, however, Adorno both tries to resolve contradiction and attempts to turn living with contradiction into an ethical imperative. In fact, Adorno’s success lies in how he constructs multiple, dialectical arguments. He discusses aesthetic truth in ways which overlap, contradict and interplay, so that contradiction isn’t a problem and becomes a resource, which potentially informs our ethical and our political considerations. This claim clearly requires some elaboration.

Albrecht Wellmer, who writes extensively about Adorno, argues that ‘[n]o one has succeeded better than Theodor W. Adorno in analysing modern culture with all its ambiguities – ambiguities which herald the possible unleashing of aesthetic and communicative potentials as well as the possibility of a withering away of culture’ (ibid.). Adorno examines the ambiguities of modern culture at length in his posthumously published Aesthetic Theory (1970a, 1997a). In Aesthetic Theory, Adorno makes a central claim, not unlike Nietzsche’s claim about ancient Greek art in The Birth of Tragedy, that a specific kind of art in modern capitalist society has an important social function. Adorno is specifically interested in the social function of what he calls ‘autonomous’ artworks. These artworks are social both historically and materially, but they have no function or meaning, they ‘step outside’ of what Adorno (rather problematically) calls ‘the constraining spell of empirical reality’ (ibid.). Because they do not use universalising conceptual language (they appear to be “meaningless”), artworks are vehicles of particularity. Adorno points out that it is an artwork’s non-conceptual language that makes it a bearer of truth.

Artworks contain the ‘capacity to express the ineffable [and] represent the unrepresentable’ (Wolin, 1992). In other words, authentic artworks do not summon concepts to mind, instead they point towards the possibility of expressing particularity. Thus, it is art’s mimetic sensuousness that refutes the universality of reason based on the processes of identity thinking which Adorno claims is fundamental to domination, repression and suffering in modernity. By refusing to communicate, authentic artworks communicate this essential truth. However, not all modern artworks are authentic. Art is authentic when it manages to (somewhat paradoxically) express, or at least hint at, both reification and reconciliation. What makes this sort of art important is its critical nature. Essentially, because they do not communicate in a conceptually meaningful way, autonomous artworks highlight the possibility for experience beyond the restrictive and damaging conventions of identity thinking. This argument leads Adorno to claim that ‘[a]rtworks must act as if the impossible were for them possible’, they aim at ‘perfection which it is impossible for them to reach’ (ibid. p.169), thus signifying that this is not all there is.

For Adorno, autonomous art ‘confronts existing society with a principle of radicality and negativity, with the postulate of the possibility of the impossible’ (Schafhausen, Muller & Hirsch, 2003 p.9) and thus, ‘truth is revealed through [artworks]’ (ibid. p. 284). Despite the all-encompassing nature of the system in which we live, where freedom, morality, the good, even ‘positive meaning’ (Adorno 1997a p. 152) are impossible, ‘art is the ever broken promise of happiness’ (ibid. p.136). Here aesthetic truth is an antidote to what Adorno, rather problematically, describes as the social ‘spell’. However, he also views truth in art as something more open and flexible, and it is here that the paradox lies. At once, autonomous art embodies the post-metaphysical, anti-essentialist negation of absolutes and, more problematically, it confronts what Adorno calls the social ‘spell’, the ‘totality’ and the all-encompassing nature of ‘what exists’.

The key to understanding Adorno’s notion of aesthetic truth lies in what he writes about the relationship between art and philosophy, and the relationship between the actual, or the social – which he calls ‘what is’, the ‘totality’, the Verblendungszusammenhang (Adorno 1973, 1997a, 1999) – and the possible, the redeemed and the reconciled. Lambert Zuidervaart comments on this relationship: ‘To the extent that disclosure of artistic truth requires philosophical interpretation, it is ultimately because of philosophy that art can express social antagonisms and suggest the possibility of reconciliation’ (Zuidervaart 1991 p. 209). Conversely, philosophy needs art in order to fulfil its purpose, to ‘break the magic spell’ (Adorno 1998 p. 13). In the essay ‘Why Still Philosophy?’, Adorno explains why art and philosophy are in this relationship. ‘What is right for art is just as right for philosophy’, he writes, ‘whose truth content converges with that of art, by virtue of the technical procedures of art diverging from those of philosophy. The undiminished suffering, fear and menace dictates that the thought that cannot be realised should not be discarded’ (ibid. p. 14).

A serious problem with Adorno’s analysis of the social function of art is that he employs concepts like utopia, redemption and reconciliation, which tend to take precedence over more interesting, less restrictive concepts like astonishment or shock and shudder. Adorno’s notion of aesthetic truth tends towards totalising claims, for instance he claims that society is totally dominating, which it clearly isn’t: human beings are occasionally able to make free choices, to say no to the system, despite what Adorno may claim. This flawed approach has the effect of undermining the negativity that is vital for his dialectic, and it is not at all necessary for the considerable ethical and political force in much of what he writes. A related problem is that statements like ‘artworks have no truth without determinate negation’ (ibid. p. 129) mean that Adorno has no choice but to characterise art’s social function in terms of a negative utopia. Behind this problematic view of aesthetic truth is Adorno’s assumption that somehow art offers ‘big answers’ to the big questions of philosophy, that it is possible to pose, and solve big questions about the “nature of reality”.

A major problem with Adorno’s account of aesthetic truth is that, like Pinter, he prioritises a misguided (we might call it a realist) notion of truth and thus a problematic notion of redemption which he really doesn’t need. The reasons why Adorno pursues this notion of redemption are to be found primarily in his relationship with certain materialist and messianic aspects of the work of Marx and Walter Benjamin.  Although Adorno argues for the sake of maintaining his all important dialectic, that we should not let thought ‘atrophy’ (Adorno 1998 292-3) at the same time he allows his own thought to distance itself from the negativity required to resist ‘atrophy’ (ibid.) by taking a problematic, absolutist position when he writes about aesthetic truth. So why does Adorno, like Pinter, counter absolutism with absolutism? Here, we again find the paradox that we find in Pinter; Adorno employs absolutist concepts in order to undermine the absolute nature of what he calls the totality. The problem is that Adorno takes his negativity into the theological. This sort of language is the only way in which it is possible to question what he believes to be the absolute nature of the social totality. Thus, because Adorno attaches theological implications to what he says about the critical social role of autonomous art, he forfeits the negativity that makes his work critical in the way he wishes it to be. The question is: does, or can, Adorno reconcile redemption with his negative dialectic? Is this theological, messianic impulse necessary? As Raymond Geuss writes, ‘it would be a shame if it turned out to the case that Adorno remained dependent on the tired, diffuse Romantic religiosity from which it was one of the glories of the twentieth century to have freed us’ (Geuss 2005 p. 247). I would argue that no, Adorno does not need this theological messianic impulse, it is both unnecessary and misguided. But it does show us something interesting about philosophy, the ethical and the political.

Although Adorno argues for the sake of maintaining his all important dialectic, that we should not let thought ‘atrophy’ (Adorno 1998 292-3) at the same time he allows his own thought to distance itself from the negativity required to resist ‘atrophy’ (ibid.) by taking a problematic, absolutist position when he writes about aesthetic truth. So why does Adorno, like Pinter, counter absolutism with absolutism? Here, we again find the paradox that we find in Pinter; Adorno employs absolutist concepts in order to undermine the absolute nature of what he calls the totality. The problem is that Adorno takes his negativity into the theological. This sort of language is the only way in which it is possible to question what he believes to be the absolute nature of the social totality. Thus, because Adorno attaches theological implications to what he says about the critical social role of autonomous art, he forfeits the negativity that makes his work critical in the way he wishes it to be. The question is: does, or can, Adorno reconcile redemption with his negative dialectic? Is this theological, messianic impulse necessary? As Raymond Geuss writes, ‘it would be a shame if it turned out to the case that Adorno remained dependent on the tired, diffuse Romantic religiosity from which it was one of the glories of the twentieth century to have freed us’ (Geuss 2005 p. 247). I would argue that no, Adorno does not need this theological messianic impulse, it is both unnecessary and misguided. But it does show us something interesting about philosophy, the ethical and the political.

A central issue here is that Adorno often tries to make a strong claim out of a more interesting weak one. He tends to turn his interesting claims about the social role of art into unproductive metaphysical claims about redemption and reconciliation, rather than exploring the less structured or rigid possibilities suggested by these concepts. In Minima Moralia (1999), Adorno is clearly aware of doing this. ‘Did not Karl Kraus, Kafka, even Proust prejudice and falsify the image of the world in order to shake off falsehood and prejudice?’ (Adorno 1999 p.72). Despite this self-awareness, the problem is that this tendency to totalise obscures his more interesting arguments. On the other hand, Adorno’s less structured, anti-essentialist approach is reflected in his productive notion of art’s cognitive potential, where ‘thinking empirical incommensurability’ criticises identity thinking. Here, what Adorno says about aesthetic experience can direct and enrich how we think about experience in general. We find this experimentalism in this wonderful line from Minima Moralia: ‘[t]he task of art today is to bring chaos into order’ (Adorno 1999 p.222).

This contradiction creates a tension of some interest. Essentially, Adorno’s notion of aesthetic truth is paradoxical; he at the same time tries to think in absolutes and he attempts to undermine absolutism. However, unlike Pinter, Adorno does not attempt to resolve this tension. Indeed, for Adorno it is an imperative that such tensions should be sustained rather than resolved, despite the theoretical paradoxes that may ensue. Adorno’s refusal to resolve the paradoxes in Aesthetic Theory is significant because it shows us that thinking in absolutes is ultimately bound to fail. The point here is if we no longer see the need for thinking in absolutes, what we have left is merely a question: what do we do? Gadamer points out that we should ask this more productive question, which concerns ‘the sense of what is feasible, what is possible, what is correct, here and now. The philosopher of all people, must, I think, be aware of this tension between what he claims to achieve and the reality in which he finds himself’ (ibid.). This tension is central to the successes and inadequacies in Adorno’s account of aesthetic truth. In Aesthetic Theory this tension manifests itself as a theme of struggle and inevitable failure, and of the consequent struggle between the denial of, and acceptance of, that failure. Despite (and perhaps because of) its metaphysical implications, Aesthetic Theory’s key point is that art’s great achievement lies in its failure. Art ‘signals the possibility of the non-existing’ (ibid. p. 132) but fails to give us what it promises.

However, in this failure also lies art’s success. It is because of this failure that we keep trying, that we don’t give up, that we can go on. It is only when we try, and inevitably fail, that we can “let go” of absolutism and turn to Gadamer’s ‘weak’ ethical question of what we should do here and now. Perhaps, in the light of this failure, we are able to consider what we should do, in ethical social and political terms, without recourse to final resolution, to strong arguments and big answers. When he writes about the possibility of the impossible, Adorno is trying to capture this moment of anti-absolutism. This is why the concept of negation is important for him. IT is also why resolution is not necessarily a good thing. It is in this moment of openness, similar to the one we find in Gadamer’s hermeneutic notion of play (Gadamer 2004), that we experience non-identity; here we do not have to, or need to ‘take a standpoint’ (Adorno 1973, p 5). In the negation of absolutes, in the non-identical, we find the space for reflection, speculation, interpretation, and thus perhaps for experience of the other, freedom and the good.

There are further implications of privileging absolutism, particularly when conceptions of the political are at stake. For instance, although the American pragmatist Richard Rorty would agree with Pinter that the desire to ‘uncover’ truth is often the binding principle of a community committed to democracy, he argues that this is actually a counter-productive way of doing politics. Rorty’s criticism here is based on his more general argument, considered earlier that truth is a ‘contingent’ property of language rather than something that ‘corresponds to facts’ or that is ‘discovered’ (Rorty 1989 p. 9). Given the premise that truth is ‘agreement among human beings about what to do’ (Rorty 1999 p. xxv), ‘[t]he more of that truth we uncover, the more common ground we shall share and the more tolerant and inclusivist we shall become’ (Brandom, 2000 p. 1).  However, for Rorty, the desire for an ‘object cannot be made relevant to democratic politics’ (ibid. p. 2) and truth in the sense of correspondence is such an object. Instead of trying to uncover truth, we should be working out how to reach a temporary consensus on justified belief, in terms of what is true for now. Perhaps Pinter would argue here with the urgency of political struggle in mind; we can only win the battle for truth by responding to the (false) truth-claims of the powerful with our own (true) truth-claims. However, Rorty would respond by questioning why we need these sort of truth claims at all. Rorty suggests that thinking about truth in this way, is essentially thinking about truth as redemption. For Rorty, redemptive truth is

However, for Rorty, the desire for an ‘object cannot be made relevant to democratic politics’ (ibid. p. 2) and truth in the sense of correspondence is such an object. Instead of trying to uncover truth, we should be working out how to reach a temporary consensus on justified belief, in terms of what is true for now. Perhaps Pinter would argue here with the urgency of political struggle in mind; we can only win the battle for truth by responding to the (false) truth-claims of the powerful with our own (true) truth-claims. However, Rorty would respond by questioning why we need these sort of truth claims at all. Rorty suggests that thinking about truth in this way, is essentially thinking about truth as redemption. For Rorty, redemptive truth is

…a set of beliefs which would end, once and for all, the process of reflection on what we do with ourselves. Redemptive truth would not consist in theories about how things interact causally, but instead would fulfil the need that religion and philosophy have attempted to satisfy. This is the need to fit everything into a single context, a context that will somehow reveal itself as natural, destined and unique (Rorty 2000 p.1).

What is particularly interesting in Pinter’s speech is his view that, in the end, truth is a redemptive force. Redemption here is a sort of rescuing, a recovering of something that has been lost. Pinter argues that if we assert the truth we can counter the immorality of untruth. If we do this, we recover our dignity and thus individual and community are redeemed.

Clearly, Pinter is trying to fit everything into the single, specific context of what he believes to be the ‘real’ truth. But, however much we want to, we can never claim to have the complete picture, we can never obtain the absolute. All we have is language, which we use to describe the world and orient ourselves within it. In Holzwege (1959, 2002) Heidegger argues that modernity is characterised by the ‘conquest of the world picture’ (Heidegger 2002 p. 67). He claims that the ‘essence’ of modernity (ibid.) is the objectifying, institutional research mode of explaining and understanding the world. This leads us to believe we can ‘represent’ the world through ‘the unlimited process of calculation, planning and breeding’ (ibid. p.71).  This damaging objectification of things, and ultimately ourselves, is characterised through a ‘battle of world views’, with each world view believing itself to be the correct picture of reality. Like Rorty, Heidegger claims that the problem is the belief that we can accurately picture reality. Human beings dominate and master beings ‘as a whole’ because their relationship with other beings is inauthentic, they have forgotten that they share an essential Dasein with all other beings in the world. For Heidegger, technology, scientific research discourse and the related objectification of the world have made humanity forget its authentic Being, its ‘is-ness’ that it shares with all other beings. One way to counter this drive for ‘picturing’ for Heidegger is the quest for ‘authenticity’, which involves ‘creative questioning and forming from out of the power of genuine reflection. Reflection transports the man of the future into that “in-between” in which he belongs to being and yet, amidst beings, remains a stranger’ (ibid. p.72).

This damaging objectification of things, and ultimately ourselves, is characterised through a ‘battle of world views’, with each world view believing itself to be the correct picture of reality. Like Rorty, Heidegger claims that the problem is the belief that we can accurately picture reality. Human beings dominate and master beings ‘as a whole’ because their relationship with other beings is inauthentic, they have forgotten that they share an essential Dasein with all other beings in the world. For Heidegger, technology, scientific research discourse and the related objectification of the world have made humanity forget its authentic Being, its ‘is-ness’ that it shares with all other beings. One way to counter this drive for ‘picturing’ for Heidegger is the quest for ‘authenticity’, which involves ‘creative questioning and forming from out of the power of genuine reflection. Reflection transports the man of the future into that “in-between” in which he belongs to being and yet, amidst beings, remains a stranger’ (ibid. p.72).

The claim Heidegger makes here about reflection is interesting for our understanding of the role and limits of politics and philosophy. The problem arises when, like Pinter, we privilege redemptive truth in political and philosophical discourse. Paradoxically, the downfall of political and philosophical language lies in the claim that they are privileged discourses, because this assumes that they can get to ‘the truth’. Similarly, although Pinter privileges political discourse over artistic language in his claim about the redemptive nature of political realism, he paradoxically exposes the essential poverty of the discourse he privileges. In fact, as the writer Siri Hustvedt argues in a similar vein to the phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, ‘language can’t be disentangled from seeing and recognition. When Marco Polo first saw a rhinoceros on Java, he recognised it as a unicorn’ (Hustvedt 2003). Of course, we now know that a rhino is not a unicorn. Thus,

…nobody sees everything. All vision is partial, as is every descriptive sentence. We are all a bit blind, and when we tell a story, we all leave out parts of it. If language orients vision and words create pictures, then the reliable cliché crumbles to bits, and we find ourselves in another landscape altogether – a mysterious island where we must always be on the lookout for unicorns (ibid.)

This is the sort of landscape in which it is possible to imagine Heidegger’s stranger; such a place requires the creative reflection of the imagination. There is an interesting affinity here with a major subtext in Adorno’s Minima Moralia (1999), a book which concerns itself with the notion of exile and what it means to live in a strange culture. Although his notion of the ‘totality’, or the ‘spell’ is problematic because of its tendency to totalise, something of interest can be gleaned from what Adorno says about the potential for individual freedom, represented by the strangeness of the emigré experience. Adorno writes, ‘Every intellectual in emigration…lives in an environment that must remain incomprehensible to him’ (Adorno 1999 p. 33). Although Adorno writes of the experience of exile as a negative and stifling one, because of his insistence on the dialectic we are constantly reminded of the possibility for freedom of expression and creativity that exile brings.

Perhaps, in the moment of chance, of creativity, of naming a unicorn, we might experience otherness. We could say, then, that it is in the gaps that we find the good, even if Adorno does insist that modern life is irreparably damaged and hence ‘in the bad life a good life is not possible’ (Adorno 2001b p. 167). For Adorno, then, the key to drawing out the implications of these ideas can be found in the incommensurable or non-identical in art. What is important here is that what might be called imagination, or creative ambiguity – despite Pinter’s objections – does have a distinctly ethical edge because it criticises the limits of redemptive absolutist thinking and opens up possibilities for thinking and practice. The Iranian writer Azar Nafisi paraphrases Adorno when she argues that ‘ “The highest form of morality is not to feel at home in one’s own home”…most great works of the imagination…always forced us to question what we took for granted. It questions traditions and expectations when they seemed too immutable’ (Nafisi 2003 p.94). Adorno himself writes, in the appropriately titled ‘Gaps’ in Minima Moralia, ‘the value of a thought is measured by its distance from the continuity of the familiar (Adorno 1999 p. 80).

However, this sort of anti-essentialism can easily be sacrificed by pursuing truth as a redemptive force. This feeling of in-between, of gaps, of what Pinter calls ‘never ending reflections’ (Pinter 2005 p. 13), constitutes an openness, an uncertainty, a capacity for imagination. Anti-essentialism not only exposes the poverty of redemptive language that can lead to entrenched religious, moral and political positions. It also advocates the kind of ethical deliberation that Iris Murdoch refers to in her claim that moral reasoning is not a ‘privileged activity’ done by philosophers, but should instead be thought of as something that we all do, in everyday life. Certainly, Murdoch would agree with Heidegger’s claim that ‘[r]eflection is the courage to put up for question the truth of one’s own presuppositions and the space of one’s own goals’ (Heidegger 2002 p. 57).

However, this sort of anti-essentialism can easily be sacrificed by pursuing truth as a redemptive force. This feeling of in-between, of gaps, of what Pinter calls ‘never ending reflections’ (Pinter 2005 p. 13), constitutes an openness, an uncertainty, a capacity for imagination. Anti-essentialism not only exposes the poverty of redemptive language that can lead to entrenched religious, moral and political positions. It also advocates the kind of ethical deliberation that Iris Murdoch refers to in her claim that moral reasoning is not a ‘privileged activity’ done by philosophers, but should instead be thought of as something that we all do, in everyday life. Certainly, Murdoch would agree with Heidegger’s claim that ‘[r]eflection is the courage to put up for question the truth of one’s own presuppositions and the space of one’s own goals’ (Heidegger 2002 p. 57).  On this account, our reasons for doing things are more akin to Pinter the writer’s anti-foundational claim that things can be both true and false, rather than Pinter the citizen’s desire for redemption (Pinter 2005 p. 9). Perhaps, then, Pinter is mistaken to separate his political and artistic selves; maybe his citizen could learn from his artist. For example, Pinter’s citizen could learn that politics needs more description and evaluation, more of the ambiguity, complexity and anti-essentialism common to the language of art. For Nafisi, in literature, we find ‘an affirmation of life…[which]…lies in the way the author takes control of reality by retelling it in its own way, thus creating a new world’ (Nafisi 2003 p. 47). This sort of approach is useful for thinking about how we might create a more progressive politics because the open and reflective retelling of our lives that art encourages can help us to rationalise, discuss and evaluate with more understanding and less prejudice. As Richard Rorty writes, art provides ‘glimpses of alternative ways of being human’ (Rorty 2000 p.2). This tells us that we should be aiming for more, not less uncertainty; the more alternatives and possibilities there are, the more likely we are to devise new, more productive ways of doing things.

On this account, our reasons for doing things are more akin to Pinter the writer’s anti-foundational claim that things can be both true and false, rather than Pinter the citizen’s desire for redemption (Pinter 2005 p. 9). Perhaps, then, Pinter is mistaken to separate his political and artistic selves; maybe his citizen could learn from his artist. For example, Pinter’s citizen could learn that politics needs more description and evaluation, more of the ambiguity, complexity and anti-essentialism common to the language of art. For Nafisi, in literature, we find ‘an affirmation of life…[which]…lies in the way the author takes control of reality by retelling it in its own way, thus creating a new world’ (Nafisi 2003 p. 47). This sort of approach is useful for thinking about how we might create a more progressive politics because the open and reflective retelling of our lives that art encourages can help us to rationalise, discuss and evaluate with more understanding and less prejudice. As Richard Rorty writes, art provides ‘glimpses of alternative ways of being human’ (Rorty 2000 p.2). This tells us that we should be aiming for more, not less uncertainty; the more alternatives and possibilities there are, the more likely we are to devise new, more productive ways of doing things.

Of course, the uncertainty that is required for this sort of reflective anti-essentialism is a threat to absolutism, and it is in politics that we most clearly see absolutism’s response to this threat. Absolutism comes down hard, to show it is not afraid. After all, it has redemption on its side. We only need to think of the cases of Salman Rushdie and Orhan Pamuk, two writers who, in their respective challenges to the orthodoxies of Shi’ah Islam and the Turkish state, called for more, not less, uncertainty. Because they celebrated ambiguity where there is no room for it and championed Heidegger’s ‘creative questioning’ (Heidegger 2002 p.72), both Rushdie and Pamuk were subjected to the force of absolutism. Despite Pinter’s claims to the contrary, then, perhaps pursuing redemptive truth is, in the end, less effective than looking for unicorns.

criminal

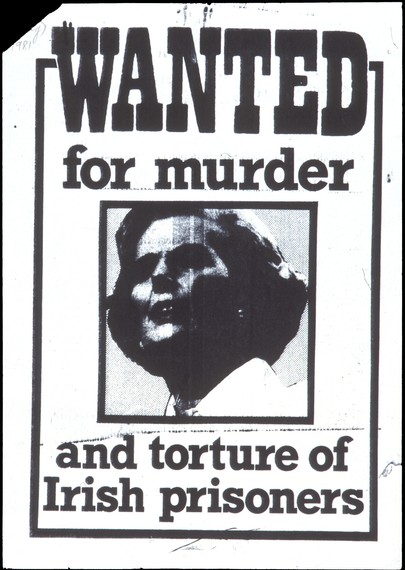

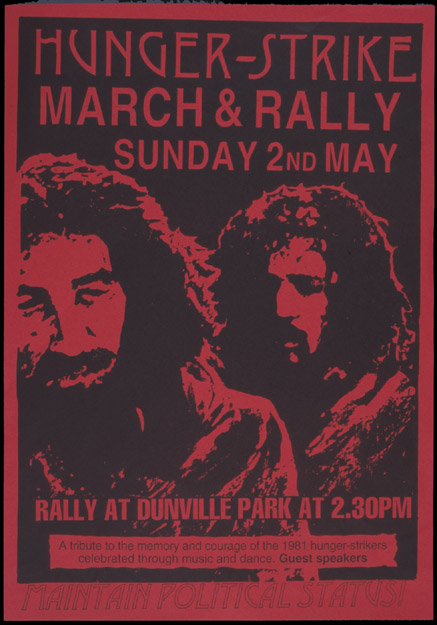

Recently I have been reading and thinking about the remarkable bravery of the men in my previous post. They died during a protest which they knew would end in their deaths. Their aim was political status, simply for recognition from the British Government that they were not ‘common criminals’. They failed, but succeeded in their goal of showing the world how brutal the British government was towards the people of Northern Ireland. I want to be able to say something about this story, but feel that it is very hard to do the protest justice without romanticising it, being a bleeding heart liberal. I also want to acknowledge the brutality of the British state in this series of events, which is not a surprise to me, but what I find uncomfortable is the fact that on a daily basis we all tacitly consent to a system capable of such brutality (and worse). What does this say about us?

The magnitude of the story of the 1981 hunger strike has never really been fully appreciated here in the UK. The republican protest of the late 70s and early 80s, including the blanket protest and the hunger strike is such a sensitive subject and I am not sure whether we, who stood by while it happened whilst being fed biased news reports, are ready to face up to the more degraded, immoral behaviour of our elected representatives and the British state. We all know it happens, but we don’t want to know that it does. This particularly dark period of modern British history is a painful reminder of what we tacitly agree to when we pay our taxes, vote or do nothing to change what is. Essentially Thatcher – who was Prime Minister at the time when the British Government was doing battle against the republican movement in the North of Ireland (whilst having secret talks with them to end the stand off) – let Bobby Sands, a member of the British Parliament, die of starvation because she refused to acknowledge that there was a political problem in Northern Ireland. Essentially Bobby S died because the Thatcher government refused to reinstate political status to the protesting prisoners. Many at the time thought the government would give in at the last minute but they did not. It was truly shocking.

I was seven years old when this story exploded round the world. I remember seeing the H blocks and the blanketmen on the news, and seeing reports when Bobby Sands died. I remember asking who he was, and why there were people living in their own excrement in prison. But I have had to seek this story out myself. This story is not something that Britain would like in its national consciousness. Perhaps one day there will be an apology / reparation of some sort from the British Prime Minister, but this will not happen for many years because it is for many reasons still clearly politically sensitive. We should be ashamed. It was Thatcher’s 85th birthday this week and David Cameron threw a party for her at number 10. The ‘great and the good’ were there, including Kelvin Mackenzie, as former editor of the Sun (1981 – 1994 – interestingly around the time of the hunger strike) one of the great opinion formers of the last 30 years (he was interviewed for the news outside no.10 looking slightly worse for wear) I have tried to get hold of the guest list for that night as it would make an interesting post but it isn’t available.

I wonder if any of the people at the party thought of Bobby Sands or of the other hunger strikers, or their families, or of how the people in the north of Ireland have suffered because of the UK’s policies towards them. Unlikely.

In my mind it is very hard to write about the 1981 Irish republican hunger strike. I have been meaning to for a while but haven’t ever found the words. I am not an expert on the politics of the situation, or the history of Ireland and its struggle with the British and am afraid of retarding the story with over-emotion and cliché, failing to do even a small amount of justice to the people who suffered. So perhaps it is a mistake to write anything at all and I should have just let the pictures in yesterday’s post speak for themselves.

In the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus the philosopher Wittegenstein writes ‘What we cannot speak of, we must pass over in silence’ (‘Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muss man schweigen’). Wittgenstein is essentially saying that some things can’t be said and is making a point about language and the ultimate meaninglessness of philosophy here. However, I think that it is easy enough to view what Wittgenstein says in an ethical light, and as such the phrase reminds me of TW Adorno’s much-hyped and misunderstood claim that there can be no poetry after Auschwitz. What Adorno means is how can we possibly do justice to the victims of the holocaust in art, or in language?  For instance think of the holocaust films that Hollywood is so fond of – the stories that these films tell can never articulate the horror of that period of Europe-wide industrial mass killing. All they really do is dilute its magnitude. We will never be able to attend to the suffering of the victims or do justice to their memory with words (or films), as there are no words to describe what they experienced, there is no way to explain it or talk about it, or even respond to it at all. And as such Wittgenstein would say we should pass over it in silence because we can’t speak of it. However if we don’t speak of it, we fail to do justice to the victims – we fail to give them a voice, the horror is forgotten, and where is the impetus to keep it from happening again? I think that the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in central Berlin captures this dilemma very well. It is a truly sensitive and thoughtful piece of public art. http://www.stiftung-denkmal.de/ (well done Berlin Town Planners for allowing that valuable piece of land to be used for a public memorial rather than sold off for development).

For instance think of the holocaust films that Hollywood is so fond of – the stories that these films tell can never articulate the horror of that period of Europe-wide industrial mass killing. All they really do is dilute its magnitude. We will never be able to attend to the suffering of the victims or do justice to their memory with words (or films), as there are no words to describe what they experienced, there is no way to explain it or talk about it, or even respond to it at all. And as such Wittgenstein would say we should pass over it in silence because we can’t speak of it. However if we don’t speak of it, we fail to do justice to the victims – we fail to give them a voice, the horror is forgotten, and where is the impetus to keep it from happening again? I think that the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in central Berlin captures this dilemma very well. It is a truly sensitive and thoughtful piece of public art. http://www.stiftung-denkmal.de/ (well done Berlin Town Planners for allowing that valuable piece of land to be used for a public memorial rather than sold off for development).

I would argue that sometimes, not always, but sometimes art, in this case cinema, can do justice to suffering. I watched Steve McQueen’s ‘Hunger’ a while ago and afterwards there was a talk by Seanna Walsh who was on the Blanket and he was utterly moved by the film – for him it captured the experience remarkably well. Of course Steve McQueen is actually an artist and it would be interesting to see what he thinks about whether art can attend to suffering in any significant way.

Here is a trailer for Hunger, if you haven’t seen it I would recommend it:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZipYYoUteCw&feature=related

And here is an article by Seanna Walsh on Bobby Sands:

http://saoirse32.blogsome.com/2005/05/05/seanna-walshs-tribute-to-bobby-sands/

So although I find it very hard to write of the 1981 protests in any coherent way, I am doing it anyway, despite my inadequacies. So why is it so hard to understand the actions of these men? They actually decided that if they had to they would die in order to expose the barbaric behaviour of the British state towards the Irish people. This decision was clearly not taken lightly, it was a last resort. They had nothing to fight with, so fought with what they had left – their bodies. During this time, there were many men on the blanket protest. With little support from outside they lived in their own shit, without any clothes, in cells with broken windows in the freezing cold, being beaten by the screws and subjected to constant harassment including internal examinations – all of this and more for up to four years. I just cannot conceive of this. The men who were on the blanket talk of how tough it was, and how their camaraderie got them through, their Irish lessons, their political education, their gallows humour. However it is beyond my comprehension how they stayed committed, strong enough to keep going. Part of their motivation was their bloody-minded determination to beat the British Government when they had themselves so many times been beaten and humiliated by its policies.

Although I am trying to say something about the protest, others can say it better, particularly with regard to why it happened. If you are interested in why, here is some background to the protest, from www.irishhungerstrike.com :

If you don’t want to read what follows, the point is that the political status of republican prisoners was taken away and the prisoners began the protest to reinstate their political status.

‘The events surrounding the prison protests, and culminating in the fast to the death of ten I.R.A(Irish Republican Army) and I.N.L.A(Irish National Liberation Army) volunteers began in 1976 when the British Government introduced a policy which was an attempt to portray Irish P.O.Ws as mere criminals. This policy became known as Criminalisation. From the 1st march 1976 any sentenced volunteer would no longer be afforded the rights of a political prisoner, a right that was won after a hungerstrike by Belfast man Billy Mc Kee in 1972,but would be treated like any other O.D.Cs(ordinary, decent criminals), as they were known. For the prisoners this would mean, wearing a prison uniform, doing prison work and a restriction in the amount of free association with their comrades inside.

This shift in policy by the British was seen by republicans as not only an attempt to criminalise the prisoners, but as an extension of this, a well thought out plan by the British government, to break the liberation struggle in Ireland. The prisons would be used as a breakers yard where the prisoners would be de-politicised, and therefore no longer a threat to the British state. The P.O.Ws had other plans. The first prisoner to be sentenced after the cut-off date was a nineteen year old Belfast man, called Kieran Nugent.He refused to wear a prison issue uniform telling the screws(warders)

“if you want me to wear a convict’s uniform you’re going to have to nail it on my back”.

His civilian clothing was thus taken away, so he sat almost twenty-fours hours a day wrapped in nothing but a prison blanket. The blanketmen, as they became known, were born. The tension within the H-Blocks soon heightened as more prisoners joined the protest, beatings became a daily occurence as the I.R.A and I.N.L.A volunteers refused to yield to the full might of the British state in Ireland.Their spirits were bowed but unbroken.

While all this was going on within the prison, the republican movement was piling on the pressure on the outside with rallies and protests in defence of the blanketmen. Rallies were organised throughout Ireland and further afield. On the military front the I.R.A had begun to target prison officers, killing several including a deputy governor.

Again the situation inside escalated and because of the severe beatings and forced mirror searches, in which prisoners would be forced to squat over a mirror in order to have their back passages probed, the P.O.Ws refused to leave their cells, unless to use the toilet. The beatings, which often led to prisoners being left unconscious, and the mirror searches, were seen by the prisoners, as a further attempt by the prison authorities to degrade them and force them into submission. A further development came when the prison authorities refused to give the prisoners an extra towel to cover themselves when they used the bathroom facilities.

This led to the no-wash protest which later became the dirty protest when prisoners, because they were being severely beaten every time they left the confines of their cells, refused to come out even to relieve their bodily functions. As a result volunteers were forced to smear their excrement on cell walls and funnel urine out the cell doors. The screws would often come along with a mop and force the pools of urine back under cell doors soaking bedding material which by this time was on the floor because all the furniture had been removed from the cells as a further punishment. After many months of living in their own excrement in scenes which the primate of all Ireland, Cardinal Tomas O’Fiaich had described as “similar to the slums of Calcutta” the prisoners decided that enough was enough and that the only way to resolve the issue was by the age old Irish weapon of last resort, the hungerstrike’.

The hunger strike was staged in order to get maximum publicity for the aims of the strike and each volunteer would start when the previous one was at death’s door. This is the list of the prisoners demands, the aim being to get political status:

1.The right not to wear a prison uniform

2.The right not to do prison work

3.The right of free association with other prisoners, and to organise educational and recreational pursuits

4.The right to one visit, one letter and one parcel per week

5. Full restoration of remission lost through the protest

Bobby Sands, who became a member of Parliament for Sinn Fein during the hunger strike, volunteered to be the first and he lasted 66 days. Thatcher didn’t budge, despite condemnation from all over the world. A further nine men died before the strike was called off. Eventually all of the demands were met, but the government never officially granted the prisoners political status. As far as I am concerned this was truly criminal.

In a sense it is the non-violent nature of this protest that makes it so significant. Particularly since these men were IRA / INLA volunteers who would have known their way around weapons more instantaneous than their own bodies.

The question here is will I ever be able to understand the need to do something like this? Would I give up my life for the greater good? For a cause that may never win? Would I ever fight like this? For instance like recent Iraqi ‘insurgents’, if my home were invaded would I would become an insurgent myself? Would I really? Would any of us? We are the rich, the comfortable early 21st Century globalised middle classes who knowingly exploit the lives of those others whose hard work and short life expectancy make our comforts so immediate, so gratifying, so fun. We are terrified of losing what we have, despite knowing that what we have is corrupted by the suffering and exploitation that can be found all through the supply chain of the goods and services we consume. We are sold a myriad of protections from chaos and death – insurance for this and that, beauty products that we are told defy the ageing process, we in the UK even pay for Trident because we (ok, some of us) choose to believe it is integral to the world’s perception of a strong Britain (without it we could be, or at least be perceived to be weak, not whatthe mightly Great Britain once was). Our existence is essentially founded on a dialectic of comfortable conformity and fear that (without ever explicitly intending to, or without me really knowing it) the massive, complex system (TW Adorno calls it the ‘Verblendungszusammenhang’ – the social web of ‘blinding coherance’) works to constantly reassure me and when it needs to it placates and distracts me. This happens because the very nature of things is that they perpetuate themselves. There is no conspiracy – there is just continuation of what is. The fact that I am aware of the way in which my conformity works makes my cowardice even more obvious to me.

As human beings we are programmed at the level of our DNA to avoid death. But these men stared death in the face, and gave in to it. It could be argued that this was because they had nothing to lose – not so. They had just as much to lose as anyone else, along with the constant temptation of giving in and being able to eat / have a clean cell/ warm clothes and so on, but they never gave up. And they did it for the greater good. They did it to hold up a mirror to the British colonial machine and its practices. To shame the British state. Bobby Sands wrote ‘our revenge will be the laughter of our children’.

Despite the fact of the utterly inspiring courage of the republican prisoners, the fact that it is so hard to say no to the system that oppresses you is key, I think, to why so few people do it. However, if we all took responsibility and said no, it wouldn’t be as hard. It is unlikely that this will happen however, with our many comforts, fears and distractions. The system won’t let us go, and we don’t want to fight it. But it is our moral responsibility to honour the sacrifice of the hunger strikers and do what we can.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2008/oct/21/northernireland-northernireland

http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2008/may/11/cannesfilmfestival.northernireland